Let’s start at the beginning: what are we talking about, exactly? Essentially, story structure is a way of understanding the different plot points that make a story compelling to an audience. Although there are many different schools of thought on the subject, for as long as people have been telling stories, they’ve followed a few familiar patterns. The diagrams below seek to make sense of those patterns and find ways to apply them.

The three-act structure

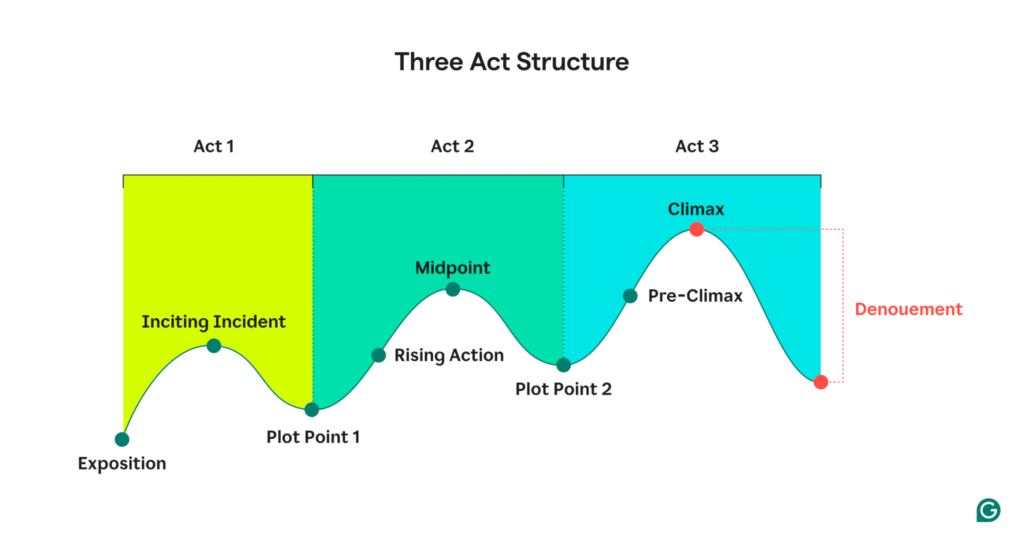

The three-act structure is a very basic one that many people are familiar with, and it’s a great tool to use as you plan your first novel. Let’s see how we could apply this structure to a familiar fairy tale, Cinderella.

The fairy tale starts by telling us how the story begins: Cinderella’s father dies after remarrying, which puts her at the mercy of her cruel stepmother and stepsisters. Their mistreatment of her has made her life miserable and relegated her to the role of a servant. This is the exposition, where we learn about the character’s world before the events of the story take place. A key element to pay attention to here is that Cinderella’s world is unhappy. To write a satisfying arc for her, her Act 3 world needs to look different from her Act 1 world. As you begin thinking about your own story structure, consider how your character’s world/circumstances/beliefs will change over the course of the story. Where do they start, and where do they end up? Cinderella’s change is positive (going from “rags to riches”), but yours doesn’t need to be.

Next is the inciting incident, which is what ultimately sets off the events of the story. For Cinderella, this is learning that there’s going to be a ball.

Plot point 1 is the moment that pushes the protagonist into Act 2 and solidifies the conflict. For Cinderella, this is the moment her stepmother tells her she can’t go to the ball. Now the story has another layer: a clear antagonist opposing the main character’s goal.

Rising action happens as Cinderella’s fairy godmother appears to get her ready for the ball, but with a warning: the magic will only last until midnight. Cinderella’s want has been met, but with conditions, and the audience can anticipate that the deadline will result in some kind of conflict.

The midpoint of the story is one of its most important plot points. Here, Cinderella attends the ball, dances with the prince, and gets to experience a moment of hope that contrasts with her Act 1 world. However, the clock striking midnight brings it all crashing down. Cinderella flees and leaves behind her glass slipper, setting up the drama of the third act. When we examine this midpoint, we’re able to see how it accomplishes a few pivotal turns in the story. Possibly most importantly, it sets up a new “want” for Cinderella. Up until now, Cinderella’s motivation was simply attending the ball, but now her attention shifts to romance with the prince (and beneath that, the possibility of escaping her current world). As you think about writing your own midpoint, start to question how this event in your story will change your protagonist’s “want”. In what ways were they seeking the wrong goal before? What makes this new goal the right one?

Plot point 2 is the moment that pushes the characters into Act 3. For Cinderella, this is when the prince announces that every girl in the kingdom will try on the glass slipper she left behind. The pre-climax comes when her evil stepmother tries to prevent her from trying the slipper on by locking her in her room. This is the moment where the suspense is at its highest. The audience wonders: will the antagonist win? Will Cinderella get what she wants?

The climax is the moment it all comes together: the evil stepmother smashes the glass slipper, but Cinderella reveals the other and tries it on, proving it’s a perfect fit. The antagonist’s attempts to thwart the hero fail, and the main conflict is resolved. As you might have guessed, the resolution is part of the story where Cinderella marries the prince and lives happily ever after.

There are limitless stories that can be looked at via this three-act lens, and doing so is a great way to familiarize yourself with how story functions! (Try analyzing some of your favorite books and movies to see if you can identify the plot points we just covered.) But this isn’t the only popular structure, so let’s examine a few others.

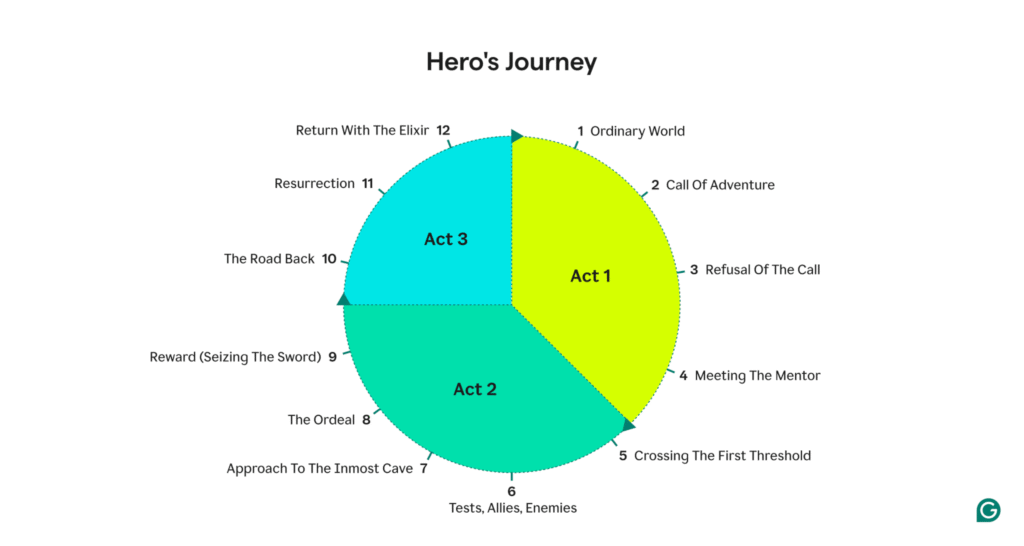

The hero’s journey

The hero’s journey is another very popular way of looking at story structure. This one is especially suited for action, adventure, and fantasy, but don’t let the use of words like “hero”, “mentor,” and “elixir” confuse you; these are really just stand-ins to describe common story beats. To show how versatile this structure is, let’s use it to examine Cinderella again!

Here, ordinary world refers to what the 3-act structure calls “exposition”. The call to adventure lines up with the “inciting incident”, learning that there’s going to be a ball. This story beat is followed by two others that the 3-act structure doesn’t include: refusal of the call and meeting the mentor. These might sound intense, but they describe common story moments that take a lot of different shapes. In Cinderella, these moments take the shape of being told she can’t go to the ball and the arrival of her fairy godmother, her “mentor”.

The mentor character is one of the most common archetypes in fiction. This is your Obi-Wan, Gandalf, Morpheus, or Cheshire Cat, journeying through the story alongside your main character and offering some form of guidance. For Cinderella, her fairy godmother gives her a much-needed makeover but also (most importantly) encouragement, helping her out of an emotional low point and preparing her for the next part of her “quest”.

Crossing the first threshold is the point where Cinderella sets out for the ball. Tests, allies, and enemies describes the conflict of the ball itself: the “enemies” of her stepmother and stepsisters, who could recognize her, and the “test” of avoiding recognition and leaving the ball before the clock strikes twelve. Approach to the inmost cave might be a confusing description for this part of the story, but this just refers to a pivotal moment in the story where the protagonist experiences something that changes everything—goals, motivations, wants, needs. For Cinderella, this is our “midpoint”, the moment she dances with the prince. Her dream (for the first half of the story) has come true. This can be a hopeful moment, like it is for Cinderella, or it can be more frightening or action-filled. Ultimately, though, this is the moment where your readers’ anticipation should be at its highest.

The Ordeal is the clock striking twelve. All that rising tension culminates, and Cinderella has to flee the ball and leave the prince (and her glass slipper) behind.

Reward (seizing the sword) might be another confusing name, but this one is simple too. This just refers to a moment the character rallies and takes action towards their new goal. In other stories, it can be a more dramatic beat where a character literally “seizes a sword”, but for Cinderella, this is simply when she learns that all the women in the kingdom will try on the glass slipper. Here her desire to be with the prince (her new goal) solidifies, and seems to be within her reach.

Her stepmother destroys the glass slipper that was left behind, but resurrection is the moment where Cinderella reveals the second one and puts it on. Return with the elixir is the last story beat, which in the 3-act structure is simply the “resolution”. Cinderella leaves the action of the story and returns to normal life, but her circumstances have completely changed, thanks to the “elixir” (the prince) as well as the experiences that have strengthened and tested her throughout her “journey”.

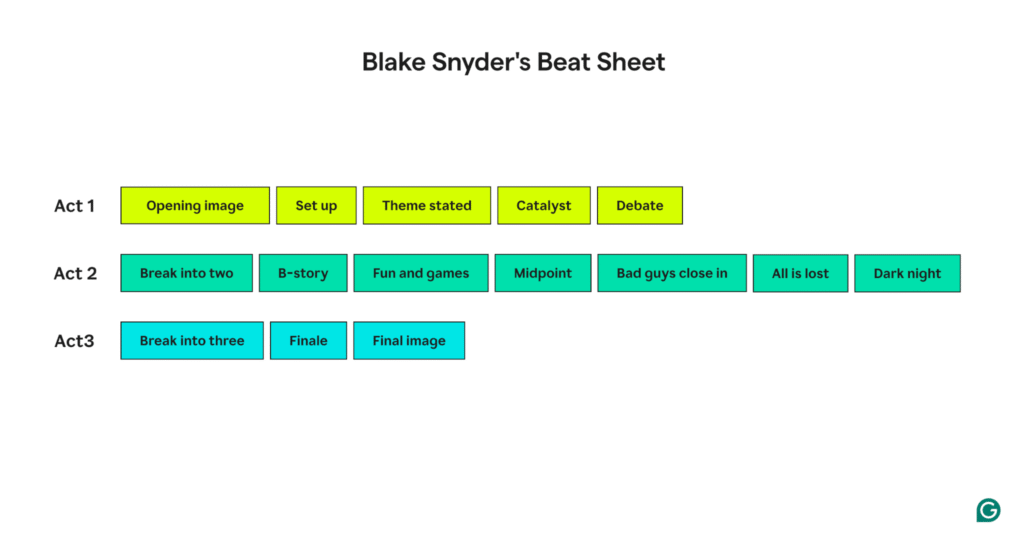

Save the cat!

The Save the Cat! story structure, originally developed by Blake Snyder for scriptwriting, has gained increasing popularity in the last few years. It’s definitely one of my favorites due to how it simplifies the different story beats and makes outlining feel more approachable. Jessica Brody, author of Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, did a fantastic job of translating Snyder’s method to from scripts to novels.

Opening image, like “exposition” and “ordinary world” in the last two structures, is what introduces us to the story and the protagonist. I love the way Brody describes this specific beat:

In simplest terms, the Opening Image is a “before” snapshot. It’s a scene or chapter that depicts your hero’s life before you’ve gotten in there as the writer to shake things up. This beat helps the reader of your story understand exactly what kind of journey they’re about to go on and who they’re about to go on it with.

The Opening Image is also what sets the book’s tone, style, and mood. If it’s a funny book, this beat should be funny. If it’s a suspenseful book, this beat should be—surprise!—suspenseful. This is where your voice (or writing style) as the author shines bright and gives the reader a clear picture of what they’re getting into.

Theme stated is something we haven’t seen on our other story structures so far. In Save the Cat!, this is a moment where another character makes a statement or poses a question, which the protagonist rejects, ignores, or doesn’t understand. This is the moment that sets up the theme of your story, the overarching arc that ultimately brings everything full-circle. In The Hunger Games, this is the moment where Gale suggests that him and Katniss run away before the reaping, foreshadowing rebellion that she isn’t ready to risk yet. In Pride and Prejudice, this is the moment where Mary says, “Pride is a very common failing, I believe”—a sentiment Elizabeth can’t agree with yet.

The Theme Stated is a single-scene beat. It usually comes and goes very quickly. The theme is stated and the story moves on. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be a person who states the theme. Although that’s more common, I sometimes see themes stated on a billboard the hero passes or in a book or magazine the hero is reading. You can be creative in how you state your theme, just as long as you state it.

The catalyst is our “call to adventure” or “inciting incident”, but with some specific guidelines added:

The Catalyst is a single-scene beat in which something happens to the hero to send their life in an entirely new direction. Notice that I emphasize the word “to”. The Catalyst always happens to your hero. It’s something active that will bust through the status quo and send them on the road toward change.

Debate is the moment that follows where the character hesitates before Act 2. They’ve been sent reeling by the catalyst and need to make a choice, and letting them consider that choice first deepens the readers’ connection to them. It gets us in the character’s head and helps ready us for what comes next.

Break into 2 is our “crossing the threshold” moment. This is where Cinderella sets out for the ball, Katniss enters the Capitol, and Dorothy steps into colorful Oz. B-story is another new helpful beat that Save the Cat! adds. This is the moment in the story where the B-story, the secondary storyline, gets introduced or strengthened. This is when Dorothy meets her new friends and gets involved in their personal quests, or when Peeta strategically confesses love for Katniss on TV, sparking their romance subplot.

Fun and games refers to the first half of Act 2, but don’t be misled by the name! This section doesn’t have to be “fun” for your characters, just for the reader. This is where you make good on what Brody calls “the promise of the premise”. It’s the games in The Hunger Games, the exciting political space drama in Star Wars, the bleak challenge of surviving Mars in The Martian. This is where you get to include all the fun bits that make your story enjoyable to read—heists, duels, dates, clues, chase scenes.

The midpoint is a beat you should be familiar with by now, and in this structure, it kicks off the second half of Act 2: bad guys closing in. This name doesn’t have to be literal, either (although it certainly can be). This is just the moment where the story changes directions once again and the stakes get higher. In The Martian, Mark’s plans go awry and survival becomes a much more distant prospect. In The Hunger Games, more and more tributes are being picked off, which only escalates the danger for Katniss.

All is lost is the moment where the protagonist faces their biggest loss. This is Rue’s death, Cinderella’s lost glass slipper, or Dorothy’s capture by the Wicked Witch.

Basically, something must end here. Because the All Is Lost is where the old world/character/way of thinking finally dies so a new world/character/way of thinking can be born.

I like to think of the All Is Lost as yet another Catalyst. It’s an action beat that serves a very similar function to the Catalyst beat in Act 1. If the first Catalyst pushed your hero into the Debate and then into the Break Into 2, then the All is Lost will push your hero into the Dark Night of the Soul and finally into the Break Into 3.

And even though whatever happens in the All Is Lost is happening to your hero, it should be, at least somewhat, your hero’s fault. Why? Because that stubborn fool still hasn’t learned the theme!

Break into 3 is our “plot point 2” or our second “threshold”, bringing us to the finale and the final image. Here, the emphasis is on transformation and the juxtaposition of where the hero began vs. where they ended. This is where the theme is personified. Dorothy realizes there’s “no place like home”. Katniss and Peeta call the Capitol’s bluff when they decide to eat the berries together, proving that 1) she’s willing to rebel now and 2) the Capitol really can be beaten. The final image is where the story closes by showing us how fundamental this change is.

We’ve looked at these three story structures in depth, but these aren’t the only ones! There are so many different ideas about how stories work, and so many different structures (such as the Fichtean curve, Freytag’s pyramid, or Dan Harmon’s story circle, to name a few). If you’re curious about any of these other methods, or want to learn more about the ones above, check out these other resources for a good place to start!